On my retirement from teaching at Queen’s, I decided to learn to draw. I had tried fitfully, a few times over the years, to master this craft, but had repeatedly given up. This time I decided to stick with it until I either became satisfied with my drawing, quit because it would never be any good, or died: whichever came first. I worked from two excellent, very different books – Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain by Betty Edwards and Making Comics by Lynda Barry – and from classes with some fine teachers at the Kingston Seniors’ Centre. And it all made me miserable.

In the long term, I had no style, context, or ideas about what to do with my drawings once I learned how to draw them. And in the short term, proportion and perspective in particular defeated me. My childishly distorted limbs and skewed horizons filled me with shame and anger. I couldn’t understand why I couldn’t do it right – or why it mattered so much. This began to take the shape of an existential crisis, exacerbated by the irony that I had just spent 31 years teaching playwriting students how to overcome exactly this kind of frustration: to stop worrying about quality, to ignore those demonic inner voices, to feel free to write badly. Now, looking at my deformed drawings, I thought about what Professor Lazarus would advise – to keep doing it badly until it got better – but I couldn’t follow my own advice.

Last fall, I was on the point of quitting forever, when I learned of a new course at the Kingston School of Art called (coincidentally like Lynda Barry’s book) “Making Comics.” I decided to give myself one last chance, and I registered. The instructor, a local cartoonist named Colton Fox, turned out to be 45 years younger than me – teaching for the first time in his life – and exactly what I needed.

For our first activity in our first class, he pointed out the pencil and sheet of paper in front of each of us, announced that we had 15 minutes in which to draw a six-panel cartoon about our day, held up a stopwatch, and said, “Go.” As my classmates, all Colton’s age or younger (including a 16-year-old and a 12-year-old), sketched happily, I stared numbly at the blank paper. He wasn’t going to teach us to draw. Maybe he assumed we could already draw. He was going to teach us to make comics. But here I was after two years of classes, still unable to draw so much as a simple cartoon of myself raking leaves. I weighed the humiliation of leaving (and sacrificing the tuition money and admitting that I was a coward) against the humiliation of drawing terribly. I reluctantly chose the latter humiliation. And, as I began drawing terribly, I had an insight.

I have long held that if two problems arise together, they are sometimes each other’s solutions in disguise. And here I had two problems. One: I couldn’t draw. Two: I didn’t have a style, and didn’t know how to develop one. But that evening, drawing my crappy stick figures, I realized that my lack of ability to draw was my style. Your ineptitude is your style. At that moment, after two years of struggling to try to grasp how to draw, I stopped struggling, trying and grasping, and started drawing. And Colton turned out to be encouraging about my sloppy drawings of myself, for, as it turned out, he did not assume that we could already draw; he just found the question irrelevant.

That same first evening, he gave us our course assignment: over the ensuing three months, each student was to write and draw an eight-page comic book (12 pages, including the two covers), under his guidance. The younger students were naturally influenced by X-Men, Avengers, anime and so on. This old guy over here chose the tradition of 1960s “underground comix”: Gilbert Shelton’s Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, R. Crumb’s Mister Natural and Fritz the Cat, that sort of thing.

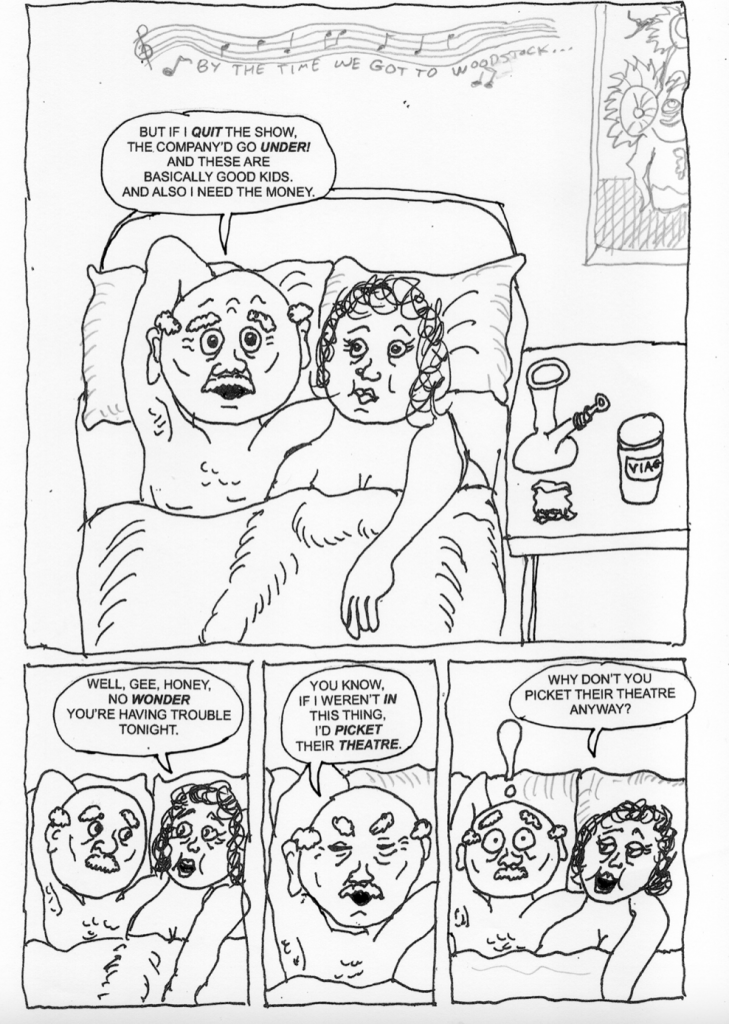

So my character is a guy from that world, now grown elderly: “Leon Schmacter, the Old Hippie Actor,” a Jewish-Canadian theatre and film performer barely scraping by in present-day Vancouver. The eight-pager, “Leon Plays a Grandpa,” was about his getting cast in a new play by progressive young liberals, only to be stereotyped as an intolerant old conservative – inspired by an anecdote I recounted in my January blog, “Old People Are So Bigoted.”

As I worked, I began to see some potential charm in the contrast between my slovenly drawing and the more experienced competence of my dialogue and plotting. It actually kind of works to have articulate social satire coming out of the mouths of these awkwardly scrawled sketches. I finished the eight-pager, gave some copies to friends, and have decided to continue working on these comics – because, most importantly, I’ve begun to enjoy the process. I’ve changed his name to Sherman Schmacter, which has more of an alliterative kick, and am busy with a 32-pager, for possible eventual publication.

It’s still a struggle. I still get discouraged. Every new drawing – of the interior of a bar, of some old people lying on Wreck Beach, of Sherman’s agent’s office – requires me to learn a new set of skills. I’ve become addicted to a huge archive on the Internet, “Drawing References,” from which I print other people’s sketches, which I then copy slavishly (and shamelessly). And, of course, I hope my cartooning will continue to improve with experience. But I’m also determined never to stop reframing my ineptitude as my style.

*****